CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY

Renovation

OVERVIEW

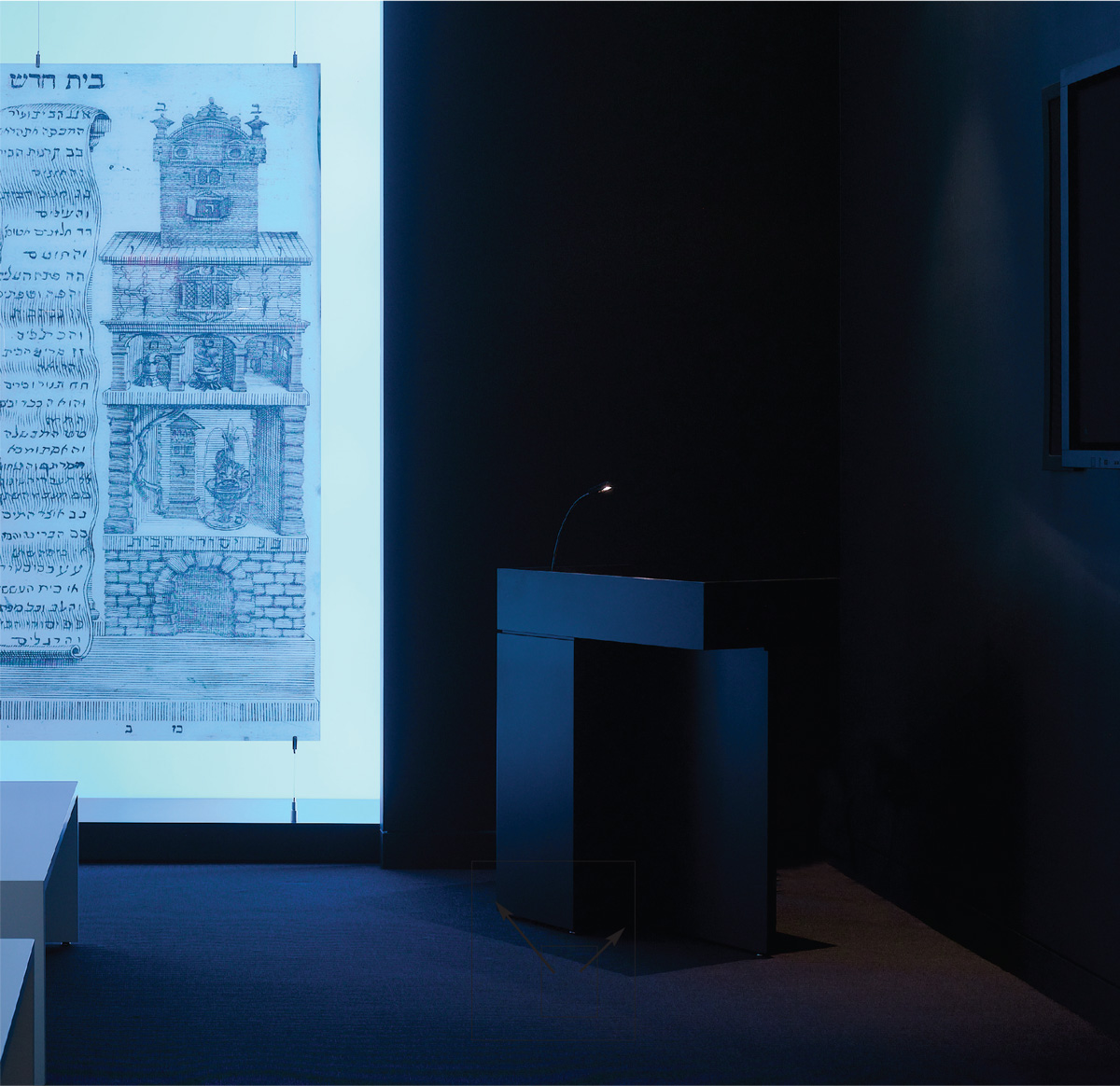

An entry installation for the downtown cultural institution was conceived as a luminous threshold, with the focal point an 18th century image comparing the areas of the human body to the rooms in a house. The illustration, attached to a massive lightbox, reflected on the space’s mirrored surfaces and a taut, glowing ceiling. The entry was designed to astonish first, then invite contemplation: “as above, so below.” Here, historical imagery and a play of light and dark transformed a once dreary passageway into another realm, provoking inquiry and meaning.

BEHIND THE DESIGN

The Center for Jewish History in New York houses five distinguished partner institutions under one roof: the American Jewish Historical Society, American Sephardi Federation, Leo Baeck Institute, Yeshiva University Museum and YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, each with vast archival collections specific to different historical regions of the Jewish people. The Center’s archives, the largest of Diaspora Jewry in the world, totals over 100 million documents, books, photographs and ephemera.

The client requested that a small storage room off the entry be used to create an orientation room to introduce first time visitors to the extraordinary richness of the Center’s resources.

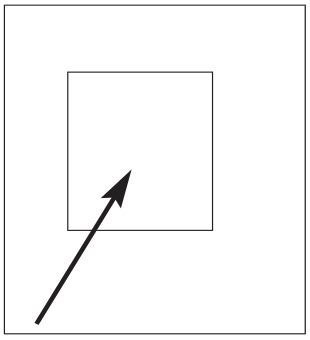

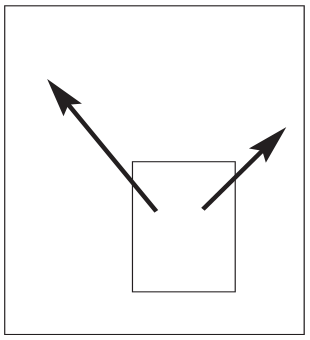

The visitor is pulled into the space by encountering Tobias ben Moses Cohn's digitally enlarged engraving from his 1707 masterwork manuscript, Ma’aseh Toviyyah, comparing the human body to a house.

The archival image soars vertically on the reflected ceiling creating a sense of spatial limitlessness, while maintaining the integrity of the details in a mirror image.

The replications of the clarity of the details are seen in all reflective surfaces unaffected by the distance from the actual image. Precise archival details move across surfaces as visitors move in space, thus engaging in a reciprocity with the archival DNA.

DESIGN SOLUTION

The concept was to transform the limited space into a theater, one that would draw visitors in with a singular compelling image from one of the partner’s archives. The dramatic effect employs one of the central ideas of the theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel, that of ‘radical amazement,’ in which one must first be amazed to want to understand.

The 300 sq. ft. space was stripped to its shell, to be free from confinement and take on the quality of limitlessness. Materials were selected for their potential non-materiality. Extraordinary lengths were taken for each invisible detail. Nothing tangible appears to exist between the viewer and the image.

Audiovisual, lighting and sound technologies were designed to pull archives from their shelves, boxes and book jackets set free for the world to see—bold and full faced—establish an encounter with even the most unsuspecting visitor, a visitor who might previously have no knowledge of the wondrous worlds of rarified materials soon to be extinct even to the most distinguished scholars, worlds which require respect and engagement to insure their being ushered carefully into the future.

The technology of this theater, its physical proportion to the technology and its layout, will allow the Center, its Partners and other participating museums to easily tap into this data base and others, creating programs that can migrate through resources without limit.

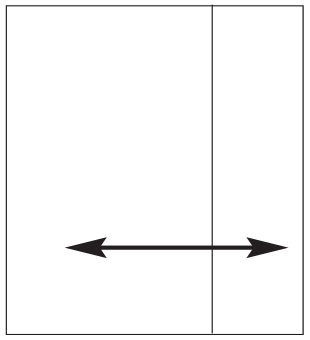

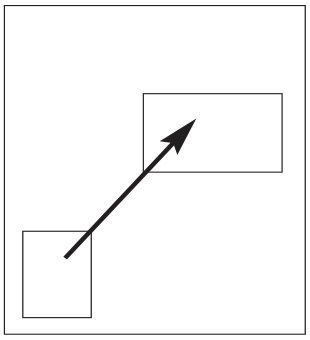

Unlike the most typical layout, seating is not set with a screen at the end of the room, seating back-to-back facing an end wall, but faces to one side, where a 65-inch high-definition plasma screen is placed on the long sidewall. Turning the space off the central axis meant introducing a dynamic equilibrium eliminating the experience of spatial confinement, an experience normally heightened by the predictability of symmetry and frontality. Here, a small, restrictive space programmed to accommodate a conventional typology takes on an unexpected, participatory complexity that invites the interaction of visitors.

Light shifts through changing hues creating a “living light” in time, joining architecture and people through the movement of light and shadow.

Materials were carefully chosen to reinforce the understatement of a muted design intended to foreground the content delivered by the plasma screen. The floor is carpeted in a ribbed nylon industrial carpet, the acoustic wall is woven vinyl with a foam backing. The ceiling is surfaced with an opaque, reflective heat shrunk vinyl over a floating frame. The enlarged archival image is a Duratran transparency floating in a field of LED digital light. The custom benches, backrest and lectern are made of MDF, with a satin lacquer finish. The entire technology is controlled from the custom lectern for the ease of a presenter, as well as from the hidden equipment rack.

The rigorous modern geometries juxtapose the old archival image in a field of enigmatic light, enhancing both the ancient and the modern realms.

BREAKTHROUGH

Our age may be rational, but many archives contained in the Center for Jewish History have a long esoteric and intellectually abstract tradition. The mission of the new Valentin M. Blavatnik Orientation Theater was not only to introduce visitors to the collections, but also to prepare them so that they could better step from the outside world into interior realms. Through an act of spatial mystification, the room is transformed into a stage for suspending disbelief. Visitors enter a space that becomes a chamber of thought and even wonder.

Like the elaborate first letter of an illuminated manuscript, this haunting enlargement of the 1707 engraving in the masterwork of the Venetian theologian and physician, Tobias ben Moses Cohn, draws people talismanically into the room, where the back-lit image floats in a mysterious field of light shifting slowly through the hues of the spectrum. The rules of spatial engagement here are to capture the mind through the imagination by an act of amazement, and, in this hypnotically luminous context, the mysterious image immediately posits a question the visitor looks to answer in the rest of the room. The space itself is next to “not there,” an otherwise darkened, apparently immaterial environment verging on nothing, simply a collage of ephemera fluctuating in a territory between reflection, glow and absolute quiet. In its planar simplicity, the room eliminates distraction, cleanses the visual palette, quiets the mind and stills the viewer into a condition of receptivity.

This archive, courtesy of YIVO, is from Tobias ben Moses Cohn's masterwork Ma'aseh Toviyyah. A progressive theologian, physician, writer, Tobias' image from his 1707 manuscript ties man to the world about him. The image is simultaneously, scholarship, theatricality and architecture.

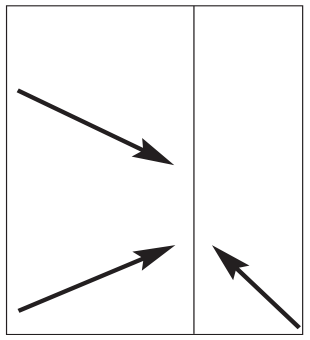

To answer the question posited by the image, visitors turn in a moment of choreography that breaks the normal frontality of a theater. At the press of a button, images flow just feet away on a thin, high-definition plasma video screen posted on a blue-black wall. “Where nothing separates the dancer from the dance,” nothing in this environment of intangibility separates the image from the viewer. The coves above the floating ceiling have dimmed, and the light in the room now comes primarily from the screen: content becomes the environment as well as message in a small space that has unexpectedly transformed from a set into a theater, in which the audience members turn to view the presentation of the plasma. Visitors are now engaged by the intimacy in an environment that is immersive. The room is not an object in itself, self-sufficient in an autonomous beauty, or commanding in its formal frontality. It is complete only when activated by people undergoing an experience usually reserved for a single scholar poring over a single page of a manuscript in a space of his own, in the quiet of his mind. The room becomes a text, and in true Talmudic tradition, a shared text. Audience becomes scholar.

The open cabinet door exposes the equipment rack, which is the epicenter of the room’s technology, including light and sound.

There are techniques for suspending disbelief. The sources of light are invisible, and light erases the edges and corners that bound the space. In their different ways, subtly reflective surfaces, and dark, matte, blue-black surfaces deepen the feeling of endlessness. The architecture disappears the into a world of subliminal effects that form a penumbra around the rolling images on the screen. Architecture fades as the images emerge in the foreground.

The medium, however, is not the message. Digital technology pulses in all the cavities behind the walls and floating ceiling, but it exists only to deliver the content. The designer has augmented that message with cultural metaphors. The reflective ceiling protects the space, like a prayer shawl, or like the luminescent cloud that covered the Mishkan, the Israelite's portable sanctuary in the desert. Light rolling away from darkness and darkness rolling away from light, makes no time like any other time. Ancient metaphors become a continuous narrative that translate into a psychological physics that comforts the space, that humanizes the technology.

The custom lectern, which recedes into the blue-black wall, controls the room’s scenes as well as the laptop presentations for the plasma screen, for the ease of the presenter.

The engraving projected onto the plasma screen is controlled through internet access from a laptop at the lectern. This manuscript is two pages from the Esslingen Mahzor, courtesy of The Jewish Theological Seminary NY. The site is made possible through the vision and generous support of George Blumenthal. When called up, the screen becomes the dominant perception in the space, with Tobias' archive receding quietly into the background.

Steeped in a rationalism deepened by the digital revolution, Modernist architects have always had difficulty conveying spirituality in a building. But the design for the Valentin M. Blavatnik Orientation Theater is an occasion to attempt to heal the split between soul and form, between the ancient and the modern, by using design to de-emphasize design in favor cultivating the message of the space. If the Enlightenment was about understanding, the design of the new orientation center restores presence and amazement to the process of learning.

“I wanted this to be a portal of radical amazement—a space of metaphors where light and reflection pull you into wonder.”